AI Regulation: Can Policy Keep Up with its Potential?

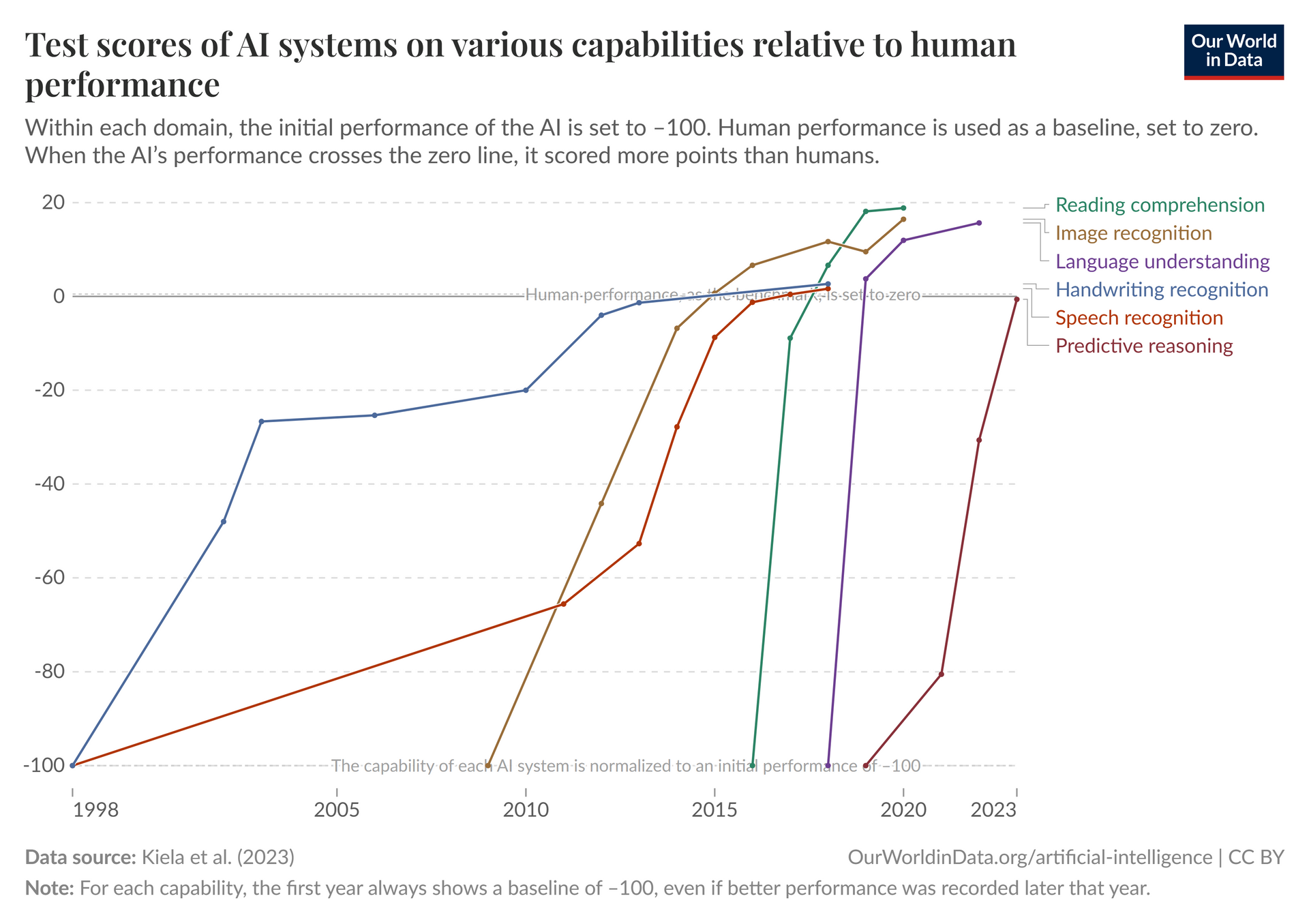

Though the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’ (AI) was first coined by John McCarthy in the 1950s, its popularity in day-to-day life, conversation, and particularly in business has seen an unprecedented explosion since the start of his decade. With this has grown the power and capacity of this technology, as the chart below demonstrates the recent rapid evolution of AI’s capabilities across reading, writing, analysis, and generation.

It comes as no surprise, then, that with this increased prevalence has come equitable anxieties regarding its potential uses and their risks. These largely surround the question-mark following this growth; in an interview with Adam Grant, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, claimed that there are ‘huge unknowns of how this is [going to] play out’: ‘[AI is] not [going to] be as big of a deal as people think, at least in the short term. Long term, everything changes.’

The antidote to these concerns? Better, robust, standardised governance to regulate this potential and bring light to these unknowns. AI at its core is a tremendously powerful force for facilitating ingenuity, efficiency, and creation, but more exacting control is required to ensure that it remains directed towards socially beneficial values and usage, and limit the potential downside imposed by serious unchecked risks.

The general assumption, spurred by quotes like Altman’s above, is that AI is an unstoppable inevitability and a possible march towards dystopia. This is not the case: AI is fettered to the people who define it and use it. In this article, we will look at the ways in which these people have approached its governance and the differing attitudes towards how important this is.

Current Approaches to Regulating Artificial Intelligence

Currently, the overarching values which govern many countries’ and unions’ approach to developing and implementing AI are the OECD’s AI Principles, which are comprised of five considerations these adherents must keep in mind, the ‘Principles’, and five recommendations the OECD makes to policy makers for applying these in practice.

With the objective of keeping AI humane, transparent, accountable, and aligned with human rights, the OECD’s Principles are as follows:

- Inclusive growth, sustainable development, and wellbeing: AI platforms should be developed for the benefit of people and the planet.

- Human rights and democratic values, including fairness, and privacy: AI engineers should internalise the law, human rights, and democratic values in their projects.

- Transparency and explainability: AI developers should disclose meaningful information and context surrounding their products.

- Robustness, safety, and security: AI systems should be secure throughout their entire lifecycle so that there is no risk to safety at any point.

- Accountability: AI actors should be accountable for the proper functioning of their products and platforms.

To this end, the OECD makes the following recommendations for nations, unions, and organisations to demonstrate these values:

- Investing in AI research and development: Governments should encourage research and development into AI tools through public and private investment.

- Fostering an inclusive AI-enabling ecosystem: Governments should ensure an inclusive, dynamic, sustainable digital ecosystem to cultivate AI development.

- Shaping an enabling interoperable governance and policy environment for AI: Governments should promote agility in order to accelerate research to deployment.

- Building human capacity and preparing for labour market transformation: Governments should collaborate with stakeholders to prepare for the changes AI will impact on work and society.

- International co-operation for trustworthy AI: Governments should work with both the OECD and each other to maximise the opportunities of AI.

At time of writing, 48 countries and one union have signed up as adherents to the OECD’s principles, representing a widespread recognition and interest in the importance of governance. However, the ways in which these different nations and bodies have filtered it into their own attempts at policy and regulation does not always demonstrate the enthusiasm to make this imminent or even obligatory. The EU AI Act, for example, was one of the first attempts to govern the usage of AI at an international level, yet its rollout has been continually delayed; and Australia have laid out eight AI Ethics Principles and an AI Safety Standard, yet these are both completely voluntary.

What this comes down to is evident: a bipedal concern between amplifying the innovation which the OECD promotes in order to maximise the potential of AI, as well as ensuring that this potential remains balanced and ethical in line with the OECD’s emphasis on doing so safely and securely. Moreover, the removal of restrictions in some regions coupled with clear misunderstandings surrounding the borderless nature of AI means that businesses and governments are focused on being first-to-market rather than the first to control values and provide the necessary guardrails to control this immensely powerful technology.

The Importance of Innovation

For many nations and legislative bodies, the reluctance to govern AI too stringently is attributed to a commitment to maintaining the space and breathability for innovators to make the most of its promise and wide-ranging potentials. The UK, for example, has resisted the publication of a comprehensive, regulated AI act for fear of weakening the country’s attractiveness to AI companies. Prime Minister of the UK, Keir Starmer, stated that ‘Instead of over-regulating these new technologies, we’re seizing the opportunities they offer’, and has unveiled the UK’s AI Opportunities Action Plan. This avoids the risk-based approach of the EU, which several have criticised for being too prescriptive, in favour of sustained economic growth by giving businesses the incentive to innovate and invest.

These commitments are founded on the principles of empowering talent and spreading the transformative effects of AI. By allowing AI entrepreneurs the power to realise their ideas without the buffer of regulation, the objective is to ensure a positive direction of these innovations from the inside out instead of projecting it externally through governance and law.

Similarly, the US, which aligns with the UK on a pro-innovation attitude towards AI, currently lacks an overarching governing principle surrounding AI, and President of the US Donald Trump has gone so far as to issue an ‘Executive Order for Removing Barriers to American Leadership in AI’ which repeals all previous policies or directives regarding its regulation. This makes it easier for developers to create AI products, platforms, and tools, especially when it comes to trialling and testing early models which otherwise risk-focused regulations would decelerate. However, given the very nature of AI and the experimentation required to develop it, the rush to deploy has left many businesses floundering with failed implementations, huge costs with little to show for it, and, in some cases, serious damage to their brands and business infrastructure.

However, as we shall cover in the next section, it is absolutely vital that this lack of regulatory control is mitigated through sound governance principles, as well as societal pressures whereby the development of AI is defined by what it should do, not what it could do.

The Pace of Change vs the Pace of Learning

However, the prioritisation of innovation over regulation raises some concerns as to the Pace of Change compared to the Pace of Learning.

Here, the Pace of Change refers to technological evolution, while the Pace of Learning represents our own human capacity to understand and remain current with these developments. These intersected in the 1950s, but the introduction of compute (the technology which established the roots of AI) caused them to widen to an almost exponential degree.

This acceleration is encouraged by policies such as the US and the UK’s which, while we hope they will ultimately bring good through the technologies and industries that they innovate, also have the potential to bring risk or harm if unchecked. In the US, the ‘Executive Order for Removing Barriers to American Leadership in AI’ replaced a more risk-based policy introduced during Joe Biden’s presidency, the ‘Executive Order for the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of AI’. Similarly, the UK’s AI Opportunities Action Plan was unveiled in lieu of ‘The Artificial Intelligence (Regulation) Bill’, an attempt to introduce more strict legislation on its use which has been continually delayed or dismissed.

Even for governing bodies which are making attempts to regulate AI and its applications, there are concerns about how successful these are in keeping stride with the Pace of Change. The EU AI Act, for example, has been criticised for its delayed and ambiguous timeline. Though it was published in March 2024, the first provisions only went into effect in February of this year, and there is uncertainty as to the rollout of its subsequent stages, providing the Pace of Change with a significant head start.

Despite this, the desire for robust governance and motivation is still present. While the EU AI Act’s phases take time to implement, the EU has introduced an ‘AI Pact’ in the interim which organisations can sign to display their endorsement of EU AI Act before it officially goes into effect. Thus far, over 200 organisations have signed this pact, representing a commitment to balancing AI innovation with security and a protection of human dignity and rights.

Conclusion

From an analysis of the different attitudes towards regulating AI laid out in this article, it is clear that there is a balance to be struck between maximising the innovative potential of AI to make a positive change, and ensuring that this change remains strictly positive through robust and holistic governance. After all, it is not necessarily the AI tools and platforms which pose the biggest risk, but those who develop and use them, and by adhering to safe and secure legislation, they can ensure that their products are engineered with people-forward principles at the forefront.

At Cambridge Management Consulting, we are equipped with the knowledge, expertise, and experience to ensure that your AI strategies remain compliant with policies and regulation to avoid penalties, and that they are built around the safety of your people and data. Get in touch now to strengthen your approach to AI that balances safety with success.

Contact Form

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Blog Subscribe

SHARE CONTENT