Legislating AI: A Comparison between the EU and the UK

The EU AI Act

In March of this year, the European Union published their Artificial Intelligence Act, establishing a common regulatory and legal framework for AI across the EU.

Two significant features of this act include the definition and prohibition of AI practices which pose an ‘unacceptable risk’; as well as the requirement for developers and ‘implementers’ to register high-risk AI models and maintain technical documentation of the model and training results.

The AI Act is the first comprehensive AI legal framework in the world. It will help to shape the digital future of the EU and guarantee the safety and fundamental rights of people and businesses.

Who does it Apply to?

The Act applies to any marketing or use of AI within the EU, regardless of whether those providers or developers are established there or in another country. While this effectively makes the act global in scope, this will depend heavily on how effectively authorities can prosecute outside of the EU.

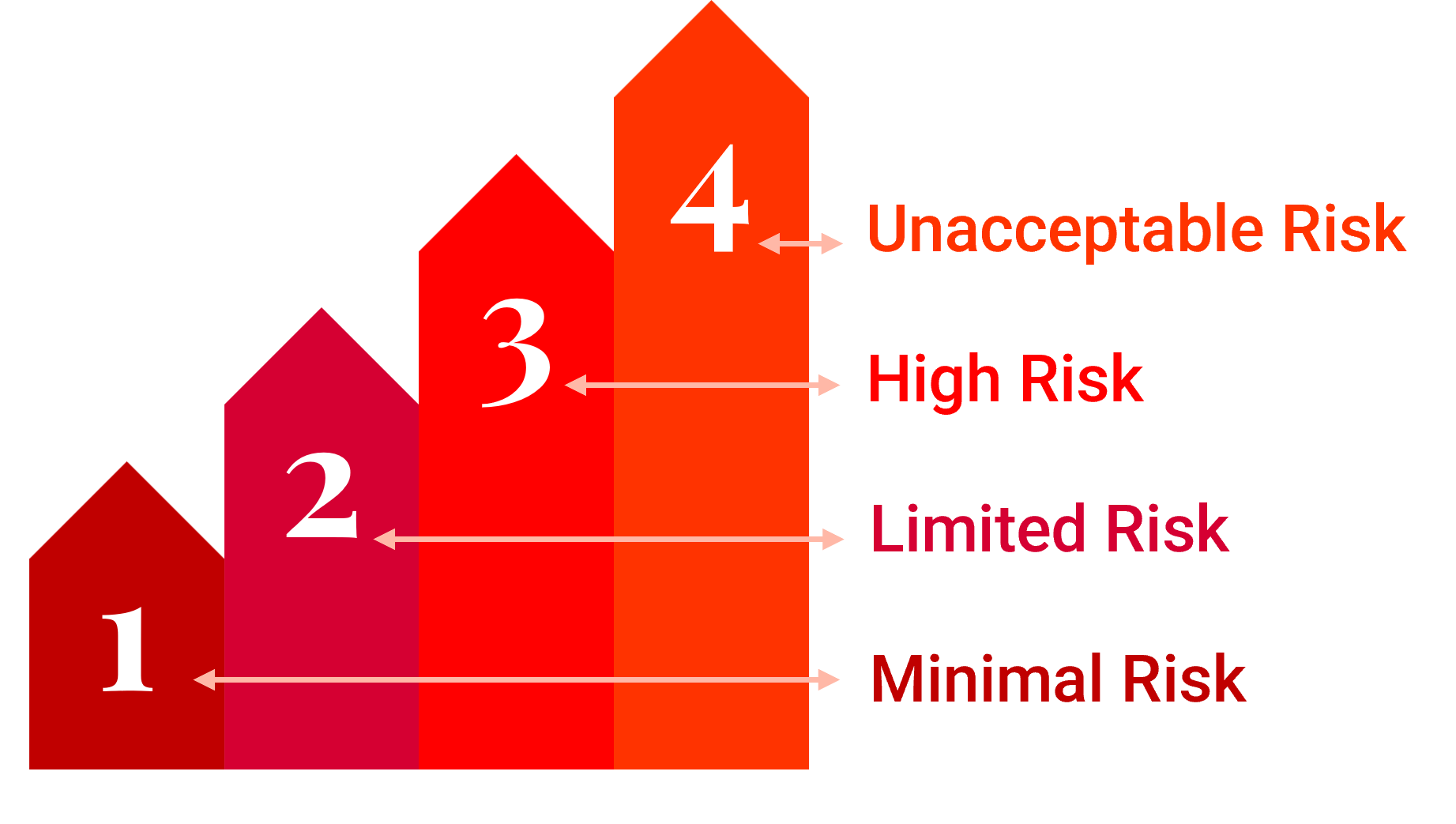

A Risk-Based Approach

The EU’s AI Act adopts a risk-based approach which categorises AI systems into different risk levels (Unacceptable, High, Limited, and Minimal Risk), and imposes corresponding regulatory requirements.

Unacceptable Risk

AI systems that pose a threat to safety, livelihoods, or individual rights will be banned. This includes, for example, government social scoring and voice-assisted toys promoting dangerous behaviour.

High Risk

AI Systems are considered High Risk if they profile individuals, i.e. the automated processing of personal data to assess various aspects of person’s life. Consequently, AI systems used in the following are categorised as High Risk: critical infrastructures like transport; education if it could affect the outcome of someone’s career, e.g., exam scoring; safety components such as AI in robot-assisted surgery; employment, where it affects selection, e.g., CV sorting; essential services like credit scoring which may affect eligibility for a loan; law enforcement, e.g., evidence evaluation; migration services which could affect asylum claims; and democratic processes such as court ruling searches.

High-risk AI technologies will be subject to strict obligations before they are allowed onto the market.

Limited Risk

Limited risk involves the risks associated with AI's lack of transparency. The AI Act mandates transparency to build trust with users. For example, users must know when they are interacting with an AI, for example when they use chatbots. Providers must label AI-generated content, including AI-generated text or media made to inform the public. This also applies to audio and video content that constitutes deep fakes.

Low Risk

The AI Act permits unrestricted use of minimal-risk AI, including AI-enabled video games and spam filters. Low Risk encompass most AI systems currently used in the EU.

Key Objectives of the EU Act

The EU’s AI Act is comprehensive and wide-reaching, however its primary principles and objectives can be summarised under three main purposes: Regulation, Trust, and Innovation.

Regulation

As aforementioned, the AI Act aims to create the first-ever legal framework for AI, addressing the risks and challenges which it has posed within its recent, rapid evolution, including the banning of those that are deemed harmful. This is particularly prescient for high-risk AI systems used in critical infrastructures, including education and employment, with the aim of maintaining their safety through conformity assessments, human monitoring, risk management, and more. Not only this, but the Act accounts for significant penalties for non-compliance, including fines of up to €35m or 7% of global revenue, which will be managed by a governance structure involving multiple entities such as the European AI Office, national authorities, and market surveillance authorities. While this appears to be a relatively complex ecosystem and may require further funding to be successful, the Act overall aligns with existing EU laws regarding data protection, privacy, and confidentiality, ensuring a cohesive regulatory environment.

Trust

In regulating AI, what has become a fast-growing industry, the Act promotes trust and transparency by making it more human-centric and with a revitalised respect for fundamental rights, safety, and ethical principles. It imposes requirements which ensure that AI systems interacting with humans are clearly identified as such, and mandates documentation and logging for high-risk AI systems. This is particularly salient for generative AI models, with specific regulations introduced to ensure compliance with EU copyright laws and ethical standards. This keeps the development of AI models in the right direction, in other words a trajectory which is ethical, beneficial to society, and contributes positively to social and economic well-being.

Innovation

Further to this, the Act maintains the momentum of AI’s development by fostering innovation and competitiveness. This will be beneficial for SMEs and start-ups, including measures to reduce administrative burdens, and promoting international cooperation and collaboration. Furthermore, the Act encourages the use of regulatory sandboxes and real-world testing environments to develop and train innovative AI systems.

The UK Government AI Framework: 5 Core Principles

The UK announced their own response to AI regulation in February of this year, in which the Rt Hon Michelle Donelan MP, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology, described her aim to produce a ‘bold and considered approach that is strongly pro-innovation and pro-safety’. As such, the Act acknowledges the rapid growth of AI, while being grounded in a risk-based approach similar to its EU counterpart. In order to address key concerns surrounding societal harms, misuse risk, and autonomy risks, the UK Act puts forward five core cross-sectorial principles to mitigate potential dangers:

- Safe, Secure & Robust: AI applications should function securely, safely, and robustly, with risks carefully managed.

- Appropriate Transparency: Organisations developing and deploying AI should be able to communicate the context in which it was used as well as the system's operation.

- Fairness: AI should comply with existing laws such as the Equality Act 2010 and UK GDPR, and not discriminate against individuals or create unfair commercial outcomes.

- Accountability & Governance: Measures are needed to ensure the appropriate oversight and clear accountability for the ways in which AI is used.

- Contestability & Redress: People need clear routes through which to dispute harmful outcomes or decisions generated by AI.

In following these values, the UK hopes to fulfil their goal ‘to make the UK a great place to build and use AI that changes our lives for the better’.

Key Differences between the UK and EU AI Legislations

The primary difference between the EU and UK’s respective approaches to AI regulation is that, where the former framework requires the introduction of a new European Agency, National Authorities, and numerous registration/compliance processes in order to operate, the latter is much more flexible. The UK Act works by asking existing regulatory bodies to interpret and adapt its regulations into their sectors.

As such, the UK framework is arguably a more practical approach, given that such entities are likely to already be considering the impact of AI. The EU AI Act, on the other hand, can be considered ‘top-heavy’, and may become bogged down in administration, only able to focus on the very big or scandalous AI incidents. It also risks becoming outdated quickly, as AI evolves and outpaces regulations.

One way to visualise this is that the EU offers a horizonal, top-down approach, while the UK is operating on a more agile, vertical system – in other words, the EU is prescriptive whereas the UK is principles-based.

This is not to say that the UK regulation is not without its drawbacks, however. It requires current regulators to quickly become more AI-savvy, and delegates the interpretation of principles to the discretion of each entity. This may produce a series of patchy or inconsistent approaches in different sectors, and it allows companies more opportunities to exploit gaps.

Summary

To conclude, though the respective EU and UK approaches to regulating the swift development of AI share certain similarities while maintaining notable differences, thus equipping them with strengths and weaknesses respective to their goals, what they both represent is a global interest in keeping AI within a strict legal and ethical framework. This is important for maintaining the safety and transparency of an industry which has the potential to introduce irreparable risk, but also seeks to increase its momentum, encouraging innovation in a way that is pragmatic, beneficial, and principled.

How we Can Help

With increased regulations comes further considerations and heightened scrutiny upon your business. AI is an increasingly prescient and useful tool, so to make sure you are utilising it to its full potential, while remaining compliant with worldwide standards, contact Cambridge Management Consulting. Our Digital & Innovation team is equipped with combined decades of real-world experience, and an acute and up-to-date knowledge on market trends, regulations, and technologies, to ensure your business is making the most of our evolving digital landscape. Contact Rachi Weerasinghe to learn more.

Contact - NIS2 Article

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Blog Subscribe

SHARE CONTENT