Do Universities Need To Be Fundamentally Re-imagined For The 21st Century?

In the second half of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st, higher education dramatically expanded in many countries, extending the prospect of a college education to increasing numbers of students from a wider array of backgrounds.[1]

Here, we look at the current situation in two major providers of higher education, the US and the UK, to draw some conclusions about how universities can (re-)position themselves for success in a climate that is much less favourable than it was when expansion began, and in which the sector is under significant financial strain.

Current Challenges

The United States

In the US, college enrolments moved into reverse in 2010, falling by an average of 1% per year since then, dramatically affecting tuition fee income, which represents the largest portion of university revenues.[2]

This fall in overall student numbers was despite an increasing US population and a rise in international students studying in the US.[3] This pain, though, has not been evenly distributed.[4] In the US, elite institutions have been largely unaffected (quite the opposite in fact), but smaller private colleges in particular have seen marked declines. A number have already folded (861 between 2004 and 2022 to be precise)[5] and some have merged in order to survive.

The forecast for others looks perilous.[6] The present outlook is not promising unless enrolments begin to increase again. Yet, state funding is now significantly lower than it was before the Great Recession and shows no sign of increasing significantly any time soon.[7] The situation is worse in some states than in others, partly because funding reductions from 2008 did not affect all states equally; for example, a number of southern states were disproportionately affected. While the overall average reduction in state funding per student between 2008 and 2018 was 13%, it was above 30% in Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi and Oklahoma.[8] To put this into perspective, at public universities, state funding covers around 50% of teaching costs.[9] Colleges have tried to compensate for declining government income by reducing staffing and restricting the programmes and services on offer, but there is now arguably little left to cut.

With concurrent increases in federal government support for individual students not having kept pace with significant rises in tuition fees, a fee ceiling has arguably been reached. Furthermore, the scale of fee rises has led to changes in the way students approach university applications, with the recent trend being for students to set their sights on a smaller number of elite institutions.[10] If you are going to pay more, you might as well aim for a better school with better career outcomes.

One recent survey put the difference in preference for a more expensive university with a good reputation, compared with going to a cheaper institution with a lesser reputation, at over ten percentage points for both prospective students and parents.[11] As some universities have pulled ahead in the enrolments game, opportunities have inevitably declined for those students with less money and capacity to travel out of state to university. General perceptions of the financial inaccessibility of a college education came out in a recent survey as the top reason why people decided not to go to college/complete their degree.[12]

The new race funded by debt

In order to try to succeed in a challenging environment, many universities in the US have embarked on costly infrastructure projects, creating something of an arms race in facilities. To put figures on this, between 2000 and 2010-11, the aggregate capital spend on new facilities was up by over 100%, at more than $11bn per year in 2010 and 2011.[13]

A report by EY-Parthenon noted that US HEI long-term debt in 2018 stood at almost $300bn, which represented an increase of 36% since 2011, dramatically at odds with the overall pattern of enrolments.[14] The same report showed that total debt was roughly equally divided between public and private institutions, despite public institutions accounting for around three quarters of total enrolments. In 2023, College Values Online reported on 30 US colleges that had changed a lot in the last five years, showing that in the vast majority of cases infrastructural improvements to academic and other facilities had been core to their approach. Aside from COVID-19-related measures, this was the stand-out takeaway of the summary. This is not to say that other things had not been done—several had increased the number of programmes on offer, improved resources devoted to student wellbeing, generated partnerships with businesses, and focussed on innovation and entrepreneurialism—but the extent to which colleges were looking to improved facilities to appeal to potential applicants was striking.[15] For those without strong endowments or public funding, this is a high-stakes approach, making failure and insolvency likely bedfellows.

The Private Equity effect

A further trend in the US has seen private equity firms acquiring universities. In 2018, an article in The Review of Financial Studies reported on 88 private equity deals involving 994 private institutions, showing that this led to increases in tuition fees and per-student debt.[16] This was coupled with lower rates of graduation, lower educational inputs, lower loan repayment rates and lower earnings among graduates, the latter possibly explained at least in part by students who would otherwise have attended community colleges being recruited to universities. In other words, there was a trade-off between value creation for the firm and value creation for the institution, particularly its students, in which the latter were the losers.

Private equity-owned institutions were also better at accessing government aid after acquisition and raising tuition fees quickly when government loan limits increased. There was a correlation between higher enrolment and an increased spend on marketing, with private equity-owned colleges employing twice as many ‘sales’ staff than other private colleges. As a result, the ratio of faculty to students and spend on tuition declined significantly following acquisition. Going forward, private equity might save struggling institutions, but the cost to students in terms of educational inputs and outcomes is likely to be high.

The United Kingdom

In the UK, private universities do not exist in the same way as in the US, and different arrangements are in place for each of the devolved nations. In England, central government funding has declined sharply in the last decade, and across the UK it was at its lowest point ever in 2021-22, according to Universities UK.[17] More widely, UK university funding is low relative to many countries: in fact, spending on tertiary education is the lowest among OECD countries. Tuition fees are also high, and only 20% of university spend is on R&D compared with an OECD average of 29%.[18] Russell Group (research intensive) universities indicate that they currently have a deficit of £1,750 per student, with this set to increase to £4,000 by 2024-25.[19]

The situation has been made particularly difficult by the marketisation of higher education in the last decade, in which caps on student numbers were removed as individual loans to students replaced government grants to universities. Already under strain, universities were forced to compete for students, with some, as in the US, investing heavily in expansion projects, especially infrastructural, creating high levels of debt in the sector.[20] In the same way as across the Atlantic, this debt could only be managed if the institution won, and continued to win, in the battle to recruit and retain students, even before COVID-19. While, unlike the US, numbers of UK enrolments have continued to increase, some universities have begun to lose applicants to competitors. In 2023, the University of East Anglia (UEA), announced a major projected budget deficit of £30m in 2023-24, a figure that it stated was likely to increase by 50% to £45m in three years; while it was trying to avoid compulsory redundancies, it could not rule them out.[21] It cited a challenging student recruitment market, leaving it down on enrolment targets/forecasts, at a cost to the institution running into millions.[22]

It was a similar story at Birkbeck in London.[23] It is currently unclear whether, in what is a relatively new market in higher education in the UK, the government at Westminster will step in to shore up institutions if they end up facing insolvency.[24] Alongside these individual instances of institutional challenges, we are beginning to see significant cracks appear more broadly: disputes about academic pay, working conditions and pensions, and cuts to staffing, are obvious and well publicised ones.[25]

General challenges to universities

In many countries, the UK and the US not excepted, wider questions have also emerged about the continued relevance of university degrees, particularly in the arts and humanities; and how well graduates are prepared for today’s working world.[26] It is likely that the move towards STEM subjects has particularly affected the smaller liberal arts colleges in the US, and it has had a significant effect on UK higher education.[27] In addition, there are now some employers who no longer require a university degree in order to apply for professional roles with them, complicating the picture further.[28] It is hard to know what effect this change will have, given how recent it is, but existing financial and other pressures already add up to something of a perfect storm for higher education providers, especially when coupled with the rise of competitive online learning companies, the increasing need to make improvements to student support and services, and a general rise in regulation.

Conclusion

There is no doubt, then, that areas of the tertiary education sector are not functioning well, for a mixture of reasons. This brings with it economic and societal costs. It is still the case that university graduates, on average, earn more in employment than their non-graduate peers: in the US, there is an average 40% pay gap between high school graduates and university graduates, while in the UK it is 30%.[29] So, if fewer students from less wealthy backgrounds attend university, income differentials will increase, to the detriment of both individuals and wider society: we are already seeing these trends among millennials in the US.[30] Furthermore, in areas with lower proportions of college graduates, outside investment is also less likely, exacerbating the problem. It is also generally bad news for economies: nations where university enrolments are falling rather than rising, and which therefore find themselves with a shortage of appropriately trained workers, are likely to see adverse economic impacts. Lack of funding for universities will also affect their ability to innovate and provide graduates with the skills that will be relevant in the economy as it changes, thus creating something of a vicious circle.[31]

How can universities respond?

Is it time for reinvention?

It would be easy to suggest that universities in the US, the UK, and many other nations, need to fundamentally reinvent themselves for a new world of learning and employment. One argument might be that they need to adopt more fully hybrid and digital learning in order to respond to increased competition in the virtual space, and hunger on the part of students for a different learning experience from the traditional university format. At the same time, it might be assumed that many of the traditional degree programmes, especially in the arts and humanities/liberal arts, are increasingly defunct in a working world for which graduates are regularly described as unprepared, and in which the skills needed are very different even from ten years ago.

It would be equally easy to point to the likelihood of better times soon as a result of the continued growth of the global (mobile) middle class and of international students from the southeast Asia and India in particular.

Both approaches are problematic. The overall growth in the number of international students in the UK and the US looks set to continue in the medium term at least, but in both countries this growth is not sufficient to offset the reductions in government funding or reverse the extent to which student aspirations have become increasingly funnelled into more elite schools and into STEM subjects. Similarly, universities in other countries are competing more strongly with the US (and the UK) than ever before; there is no guarantee therefore that universities in either country will be able to count on international students to help correct deficits in the long run.[32] In the US, this leaves struggling private colleges and state universities, which have seen steady infrastructural decline, in a precarious position that is not likely to change any time soon. State colleges might not fail entirely, but the quality of the education they offer is likely to fall significantly, disproportionately affecting particular socio-economic and racial groups. In the UK, universities with high levels of debt, and which are struggling to fill their places, are not likely to be rescued by international students.

On the other hand, while it is always important to look at things from an existential perspective and consider reinvention, it is also easy to fall into the trap of jettisoning both baby and bathwater. There are arguably many things about the traditional HE model that work well, and look set to continue to do so. In-person community is important to students (even if they are increasingly attracted to hybrid), as are career prospects and learning at a high-quality institution with high-quality course content.[33]

Furthermore, on the other side of the equation, we know that online learning provision in general is complex, requires high levels of investment, and even for specialists is not yet delivering net profit: Duolingo increased its total revenues by 47% to $369.5m in the last year, but its net loss of just under $60m was not very different from the loss it made in the year before. The growth in revenues is promising, but it remains unclear whether that will turn into net profit in the near future.[34] Pearson Education, whose initial contract with Arizona State University (ASU) was groundbreaking and helped turn ASU into a market leader in online education, has recently offloaded its online services unit to a private equity company. In a crowded and volatile market, it had not been able to keep up with competitors, and clearly did not see a profitable future for itself in online learning.[35] Pearson’s key competitors, Coursera and 2U, have not yet made a net profit, and the history of edX, bought by 2U recently, does not suggest that the viability of non-university online providers of higher education is established. In fact, most of edX’s users already had a college degree.[36] Share prices in some providers have also been falling recently after a warning by one company that ChatGPT was beginning to hurt sales.[37]

In connection with this, and crucially, it should be noted that ASU never outsourced the content of its online offering; even when working with Pearson, it produced and updated content in-house using its subject-based expertise. The fact that online success still depends on content developed and regularly refreshed by university staff indicates the extent to which the platform of delivery is just one part of a much more complex and multi-linked picture; universities remain specialists in tuition and research. One good example of how this can be highly effective is the Masters partnership between ASU and MIT which began in 2019.[38]

A more financially sustainable approach to creating the successful universities of the future

To state the obvious, there is no one-size-fits-all method that universities can adopt in order to remain/become successful. But, in a world in which interest rates are rising and liquidity in the economy is reducing, with no guarantee of increasing enrolments, taking on greater debt for infrastructural projects is likely to be high risk for all but a minority of universities – in other words, those with the biggest endowments and the largest sustained intake of students. Particularly given existing institutional debt levels, most universities would be wise to shore up operations in other ways before turning to the highest expenditure initiatives. One persistent issue that is often under-appreciated in its impact is the quality of institutional leadership and management. A series of small decisions can have a major effect when aggregated, so while getting the fundamentals of management right is not attention grabbing, it is an obvious (if far from easy) win. This is not just about inter-personal relationships within an organisation, but about strategy and operations. It is hard because it is the whole package.

A good leadership team is more likely to identify the most effective ways for the institution to move forward. Some examples of universities that have made significant strides forward in different ways in the US in recent years are the University of South Florida (USF), the University of Florida (UF) and Arizona State University (ASU).

In 2022, USF attained its highest position ever in US News and World Report rankings, and has been the fastest rising US university in rankings. The university has made major efforts in recent years to improve graduation rates, especially among low- and moderate-income students.[39] In 2010 its four-year graduation rate was 24%; by 2020 that had improved to 59% in the most recent federal statistics. Particularly notable was the success rate among Latino and black students, which was roughly equivalent to that of the student body as a whole. Key to this has been proactive support of students identified as being at risk of not graduating, a focus on improving courses with the highest rates of failure and reducing class sizes. Making it easier for students to remain on campus was another important plank of the strategy. Better graduation rates have impacted positively on recruitment too, in a self-fulfilling trend. What is interesting is the extent to which this strategy of improving graduation rates fits in with the weight the state government gives to this in its funding models, something that is not replicated in some other states.

Elsewhere in Florida, UF has similarly made a variety of improvements to its operation that have seen it rise further up the rankings, in relation to retention and graduation, class sizes, curriculum quality, in-state and out of state reputation and research expenditure.[40]

Meanwhile, at ASU, whilst it might be assumed that it is the university’s successful commitment to online education that has given it an edge on its competitors, that is only one part of the overall picture. Alongside the online offering, ASU has addressed multiple elements of its operation:

- It has reduced its reliance on state funding (at the same time maintaining the lowest tuition fees of the three state universities in Arizona)

- It has adjusted its approach to philanthropy

- It has focused on the student experience, significantly raising retention and completion rates

- It has invested in facilities

- It has aggressively increased its research income and prestige, as well as research-driven enterprise

- It has utilised big data to understand what is working well for students and what is not, and to enable interventions

- It has placed great emphasis on increasing its needs-based funds and on diversifying its student intake.[41]

In other words, ASU has taken an innovative and dynamic approach on a number of fronts without removing the core components of how a university has traditionally been defined, and it has done so successfully.[42]

The traditional model of university education can be viable, but in a world where there are few easy wins, this requires strong leadership that analyses the university’s position and does not seek to apply a one-size-fits-all model. Instead, it builds on core strengths as a collective package, and/or seeks to carve out a USP for itself based on effective analysis of its market and operating environment.

In the UK, the University of Hull is an example of a university that has had to confront major difficulties, including an unsustainable deficit, and to reimagine itself in the light of those difficulties. The process of change was inevitably painful, but the university has not only weathered the storm, it has also improved its standing markedly. How it achieved transformation is discussed with bell-like clarity by Professor Susan Lea who, as Vice Chancellor, led the institution between 2017 and 2022 when the bulk of the reforms were devised and implemented.[43] As with the US case studies, Hull did not deviate from its core mission as a university; rather, it doubled down on it.

How can other universities achieve similar success?

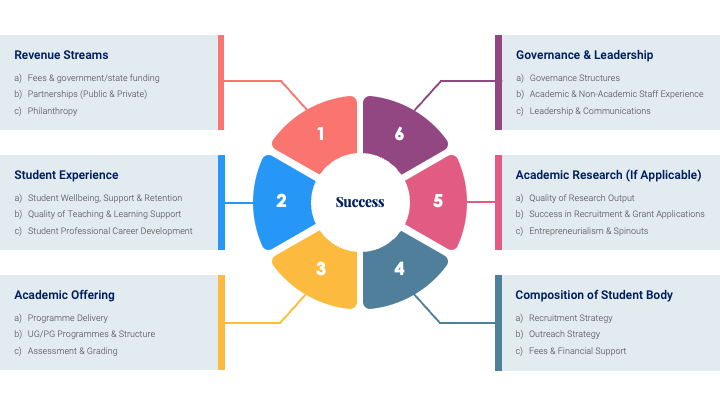

Our model below provides an outline roadmap for other institutions to work with. The starting point is that there is no urgent need for a complete existential re-thinking of what a university is. Success can follow on performing the core functions of a traditional university well. This is not to say that innovation cannot be effective – it has always in fact been at the heart of what universities are – but rather that complete re-invention is not called for.

The steps to success

Step 1: Fully assess the current situation in relation to both internal and external factors; gather and analyse data.

Internal

For example:

- Enrolments by programme

- Retention and graduation rates by programme and student type

- Financial position

- Current USP/brand/niche

- Origins of students (in-state, out of state, international, etc.), as well as their socio-economic background, ethnicity and other factors

- Where it is doing well and where it needs to improve

- Quality of leadership and management

- Quality of governance structures, engagement and communications

External

For example:

- Its market and the wider market, including opportunities for organic and inorganic growth

- Brand and Competition

- Revenue streams and opportunities to create more of these

- Its operating environment, e.g. skills needs in the region

- Relationships with external stakeholders

- Emerging trends

Step 2: Develop a strategy and implementation plan based on the above information.

The model below signals the array of factors a university leadership will need to consider as part of its overall strategic vision and action plan.

Conclusion

Higher education institutions in a number of countries face great challenges, but to imagine that now is the time to rethink the entire function of a university would be a mistake. Fundamentally, universities offer something distinct, for which it is clear that there is still a market. The concept therefore remains valuable and viable, but in a climate of declining government funding, slowing/declining enrolments and a general shift towards STEM subjects, differentiation within the range of traditional core functions will distinguish the winners from the losers. Innovation will be an important part of differentiation for universities, as it always has been, but it should never be an end in itself.

At Cambridge MC, we have the expertise to help universities pivot for a stronger future. Please get in touch if you would like to learn more about our bespoke services. Use the form below or Contact Us page.

References

[1] E. Schofer & J. W. Meyer, ‘The Worldwide Expansion in Higher Education in the Twentieth Century’, American Sociological Review, vol. 70, no.6 (2005), pp. 898-920.

[2] https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/strategy/pdf/ey-the-other-looming-educational-debt-crisis-institutional-debt.pdf?download

[3] https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/college-enrollment-decline/; https://educationdata.org/college-enrollment-statistics; https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7857/CBP-7857.pdf; https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21568235.2021.1944250

[4] https://www.publicpolicyexchange.co.uk/event.php?eventUID=NE30-PPE; https://hechingerreport.org/analysis-hundreds-of-colleges-and-universities-show-financial-warning-signs/

[5] https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-861-colleges-and-9499-campuses-have-closed-down-since-2004/

[6] https://hechingerreport.org/analysis-hundreds-of-colleges-and-universities-show-financial-warning-signs/

[7] https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2019/10/two-decades-of-change-in-federal-and-state-higher-education-funding

[8] https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-higher-education-funding-cuts-have-pushed-costs-to-students

[10] https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-higher-education-funding-cuts-have-pushed-costs-to-students

[11] https://morningconsult.com/2022/06/29/inflation-concerns-college-education-costs-reputation/

[12] https://www.highereddive.com/news/why-arent-people-going-to-college/632915/

[13] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2014/10/13/why-colleges-should-stop-splurging-on-buildings-and-start-investing-in-software/

[14] https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/strategy/pdf/ey-the-other-looming-educational-debt-crisis-institutional-debt.pdf?download

[15] https://www.collegevaluesonline.com/colleges-changes-last-five-years/

[16] https://eml.berkeley.edu/~saez/course131/Eatonetal2020privateequity.pdf: what follows is taken from the same article.

[17] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/opening-national-conversation-university

[18] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/opening-national-conversation-university

[19] https://russellgroup.ac.uk/news/russell-group-warns-of-long-term-squeeze-on-uk-skills-pipeline/

[20] https://www.fenews.co.uk/skills/uk-universities-debt-burden-grows-50-in-five-years/; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1059056022002076

[21] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-norfolk-64810537

[22] https://www.edp24.co.uk/news/23257565.university-east-anglia-set-make-job-cuts-loss/

[23] https://www.ft.com/content/25f803fd-f5cb-4577-8d86-f120ca03f6e3

[24] https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2021/09/01/why-the-government-should-never-bail-out-a-university/; https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/03/21/are-universities-really-at-risk-of-ending-up-in-the-public-sector/

[25] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9387/CBP-9387.pdf

[26] https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/news/employers-think-graduates-are-unprepared-for-the-workplace/;

[27] https://educationhub.blog.gov.uk/2021/02/09/more-young-people-are-taking-stem-subjects-than-ever-before/; https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-the-number-of-college-graduates-in-the-humanities-drops-for-the-eighth-consecutive-year/; https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/apr/4/focus-stem-education-killing-already-struggling-li/

[28] https://www.businessinsider.com/google-ibm-accenture-dell-companies-no-longer-require-college-degrees-2023-3?r=US&IR=T

[29] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/americans-are-increasingly-dubious-going-college-rcna40935; https://www.unit4.com/blog/the-us-and-uk-comparing-higher-education-in-the-two-top-ranking-nations

[30] https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/02/11/the-rising-cost-of-not-going-to-college/

[31] https://russellgroup.ac.uk/news/russell-group-warns-of-long-term-squeeze-on-uk-skills-pipeline/

[32] https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210610150037741

[33] https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/lessons-pandemic-making-most; https://tallo.com/data-insights/what-high-school-college-students-want-higher-education/

[34] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1247949/annual-duolingo-net-income/

[35] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2023/03/22/pearson-once-leader-sells-its-online-services-business

[36] https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2021/09/jhj-edx-sold

[37] https://www.ft.com/content/0db12614-324c-483c-b31c-2255e8562910

[38] https://news.asu.edu/20190619-asu-edx-and-mit-announce-innovative-stackable-online-master-science-supply-chain-management

[39] https://edsource.org/2022/how-a-florida-public-university-helps-more-students-get-to-graduation/671805. What follows is taken from the article.

[40] https://eu.gainesville.com/story/news/education/campus/2019/09/09/uf-reaches-no-7-among-top-public-schools/3457664007/

[41] https://umdearborn.edu/news/how-arizona-state-reinventing-american-university

[42] https://heeap.org/news/us-news-and-world-report-ranks-asu-ahead-stanford-mit

[43] https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Turning-Around-a-University-Lessons-from-personal-experience.pdf

Get in Touch

We have a number of specialised consulting services aimed at the public sector and universities. To find out more please get in touch below.

Contact - Africa

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Blog Subscribe

SHARE CONTENT